Curator of Corporate Character

Noyes with the IBM Design Management

Noyes in his office conference room working on Mobil gas stations

In developing a corporate design program, Noyes dove deep. searching for the essence of what that particular company was about. That then became the basis of the program he developed for that particular corporation. He sought the expertise of his peers in design reviews and to work with him on projects. Here, in such a design review with top IBM management, George Nelson is picture left of Noyes and Charles Eames (laughing) to picture right. Hidden is Edgar Kaufmann Jr.

Noyes talking about the Mobil design program with Mobil’s CEO and President

"Corporate Character" is, in essence, the core of a company. It presents a public face with an inherent message, but must accurately reflect values and workings of the corporation. Products are important but only a part of the overall character. Since no two companies are the same, Corporate Character needs to be developed individually. This, and ensuring consistency throughout the company, is no small task. Noyes applied his design skills to help corporations better define themselves.

Irwin Miller (CEO Cummins Diesel) said about Cummins Design Program:

“The design program won’t rise and fall on how it affects sales. It has to satisfy us being right. We’re going ahead on the idea that it will give us a leadership rather than being useful financially. I don’t really have much use for consumer surveys. We weren’t interested in a commercial approach, but in a thoughtful man with some personal creativity.”

Noyes said:

“It would be fine if a company could successfully handle these design matters internally and almost automatically, but this rarely seems to happen. Companies grow men skilled in business programs and not design programs. Design seems to need special guidance, often by an outside consultant. An internal staff can too easily be smothered in a corporate hierarchy and anyway tends not to have sufficient vision or authority. For these reasons, if a design program is to have a chance for success it must be initiated at the top of the company. In operation design must then be treated as a function of management, and must not be subordinate to engineering, marketing, or manufacturing functions, but must be interlocked with them as a normal part of the company’s business operations. Furthermore, the company must set up an organizational pattern and communication channels which will make this design function effective in daily relationships. Finally, the consultant must himself be a significantly good architect or designer, and in addition to this, for such a role he must be some combination of designer, philosopher, historian, educator, lecturer, and business man. He must be able to establish design standards, give direction, and provide general understanding and attitudes about design at many company levels.”

“Finally, there must, I think, be single-minded guidance of a design program, unwaveringly supported by the top management of the company. This guidance, in turn, must be exercised by someone scornful of superficial results and firm in the conscientious pursuit of excellence, which in this program is perhaps the combination of practicality and quality. In a sense, excellence should be the true goal of all such programs, if they are to be meaningful.”

Education and Curation

Bringing corporations and individuals forward in their understanding of the power and value of design takes significant effort. Noyes recognized the need for continued education to reach all corporate employee levels and the general public.

His persistence and sensible thinking eventually paid off in addressing the real issues.

Noyes said:

“During these years I did a good deal of talking about design at IBM and discussed things often with Tom Watson, Jr., (not as yet President of the company), being quite outspoken about the antediluvian and inconsistent appearance of the company as a whole.”

In speech notes Raleigh Warner (CEO Mobil Oil) wrote:

“We wanted Mobil to be a company whose products and services were consistently of the highest quality. . . we obviously were not impressing the outside world, because zoning boards all over America continued to pit service stations in the same category with junkyards. . . We needed new ways to present ourselves to the world, and those new ways would need to be designed. That is how Mobil’s design program began. . . We didn’t know much about design, but we thought we knew what we lacked. . . Ultimately, we retained Eliot Noyes to consult on architecture and industrial design, and Chermayeff and Geismar as graphic consultants. . . Eliot Noyes rather quickly set us straight concerning design as processionals look at it. He told us design is not simply a beauty treatment, but a whole process that relates objects, systems, and environments to people. The right kind of design does not concern itself only with how things look. It solves human problems.”

Noyes said:

“Meeting him (Watson) again in this context gave me the chance to explain to him that IBM needed a lot more help than just some industrial design, and I used Olivetti as an example. Along about now they discovered I was an architect as well as an industrial designer, and so I began to do small architectural and interior projects for them as well as a good deal of industrial design. I was therefore now rather active in two distinctly different professions, and this led to a third kind of activity which could be a profession in itself.”

Another example of Noyes’s effort to bring design awareness forward—in this case, by exhibit.

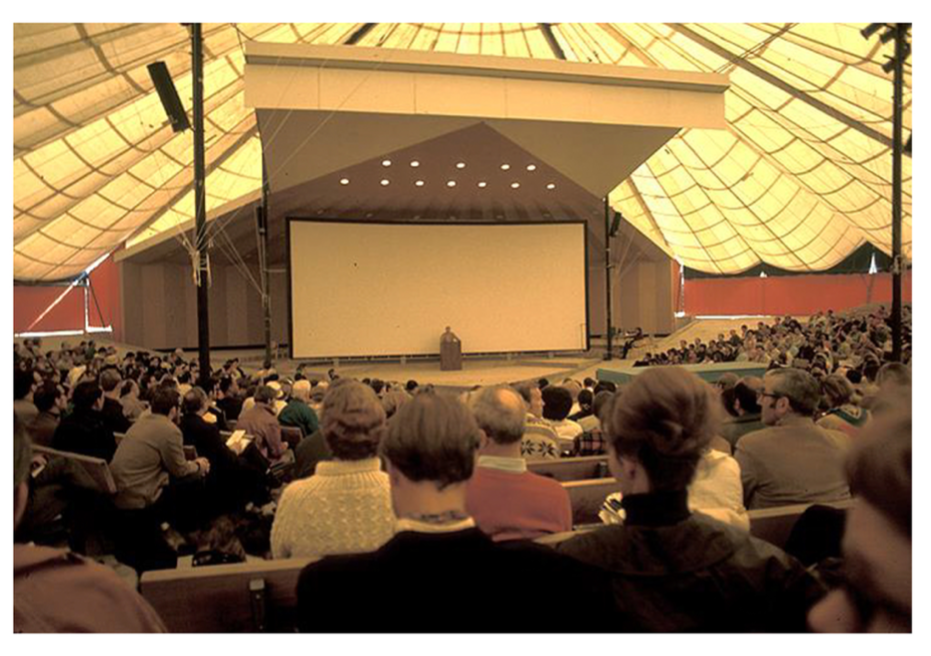

Eliot Noyes speaking to management. In-house education--at all corporate personnel levels-- was an integral part of the job. The corporations’ employees would need to pick up and expand the design programs Noyes was developing for them.

Noyes takes Raleigh Warner (CEO of Mobil) to Henry Moore’s studio to discuss art in regard to Mobil’s Fine Art Program.

A still shot from the live Television show, Omnibus, in 1955. Noyes was invited to give a talk aimed at the general public about fundamental architectural principles, in this case gravity. Moments later, he removes a bock at the tower’s base and it comes crashing down.

Noyes opens the IDCA with a bang.

A concise summary of Noyes’s design principles—as enumerated in his early 1940 exhibit at MoMA of well-designed everyday objects, none by “designers.” Note that it’s only in the 4th point where the traditional idea of design aesthetics enters.

In a ceaseless effort to encourage business leaders to better understand the power of design, and to have designers better understand the pressures on corporations, Noyes chaired the International Design Conference at Aspen (IDCA). In that, designers and executives were invited to spend a week exploring topics of mutual overlap. This photo shows the informal Aspen tents setting, conducive to easy discussion with the little inhibition of formality.